Trends in Breeding Flowering Garden Plants with emphasis on Garden Rose Breeding

David H. Byrne

Rosa Breeding and Genetics, Horticultural Sciences , Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas, USA

Abstract

Rose breeding, as with other ornamental breeding, was greatly stimulated with the advent of good variety protection laws. Currently, ornamental breeding is done mainly by the private breeders which includes large breeding companies but also a group of creative small breeding companies, independent breeders and even hobbyists who have made significant contributions to our palate of ornamental cultivars. The public breeding and research efforts although they have contributed greatly to our understanding of ornamental breeding, genetics and germplasm have been decreasing their activities due to diminished governmental funding available. Ornamental breeding objectives are greatly influenced by broad trends such as the public’s awareness of environmental issues and the consumer’s desire for convenience. Breeders need to satisfy both the needs of the consumer and of the producer. Thus they need to create novel ornamental cultivars that are well adapted to their environment, display their ornamental characteristics as long as possible, are easy to propagate and behave well during storage or transport to the market. As ornamental breeders work with hundreds of species in their work the available diversity is tremendous. The use of marker assisted selection and other newer breeding approaches is beginning to be used on some important ornamental crops such as rose, chrysanthemum, carnation among others to accelerate the progress of developing better cultivars. Nevertheless, for the majority of the hundreds of species used in ornamental breeding for which wide diversity exists and little is known about their genetic composition, the main approach to create new cultivars is traditional breeding complemented with interspecific and/or intergeneric hybridization.

Keywords: Rosa, ornamental plants, consumer preference, plant protection, patent

Introduction

Research and the development of new plants for commercial exploitation was stimulated by improved plant protection legislation in the USA, Europe, and throughout the world. In the USA, the use of plant variety protection has increased considerably since the 1990s. In the 20 year period from 1990 to 2010, over 35,000 plant variety protections were awarded in the USA. Horticultural crops accounted for 77% of these protections with the great majority of these being Plant Patents for vegetatively propagated plants. A recent analysis, has indicated that a plant patent gives the seller a sizable price premium although the degree varies with the species (Drew et al., 2010). For roses in the USA, the number of patents (both domestic and foreign) since the 1990s has fluctuated widely from 26 to 130 patents per year with an average of 78 patents per year. In addition to this there are an equal number or more roses that are registered with the American Rose Society per year of which many are not patented. Thus the rose variety offerings are constantly in flux indicating a very active breeding community (Byrne, 2015).

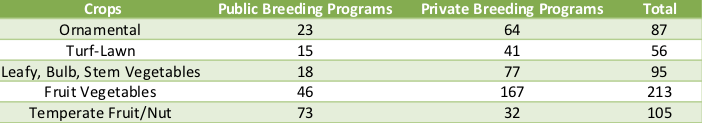

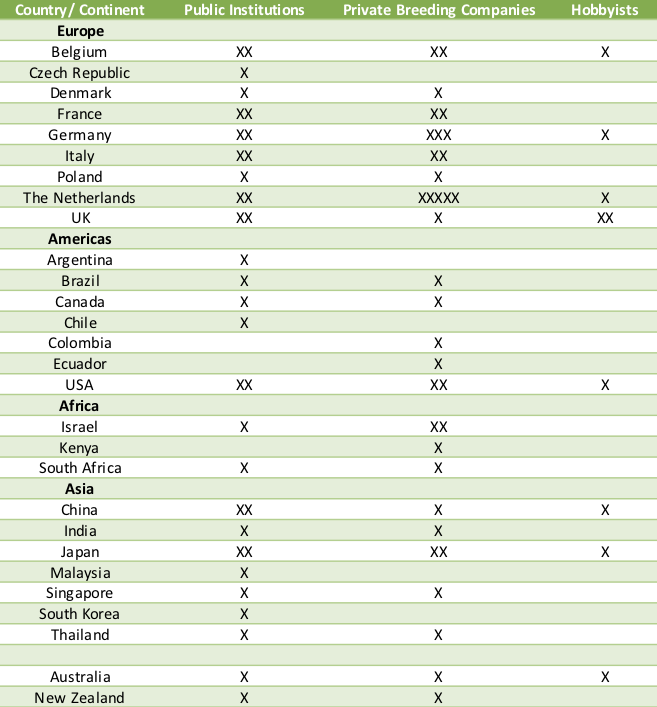

Along with this came a shift of the breeding programs from the public to the private sector (Frey, 1996; Traxler 1999; Heisey et al., 2001; van Tuyl, 2012).This shift was quicker for the annual large acreage crops such as corn, where public generated commercial cultivars in the USA disappeared in the 1940s and the use of publicly generated inbred lines ceased in the 1970s. In most countries, the private effort in ornamental breeding is much greater than that seen in the public sector (federal and state institutions, botanical gardens, hobbyists) and the majority of new cultivars used commercially are produced by private ornamental breeding programs (Frey, 1996; van Tuyl, 2012; Tables 1 and2). In parallel to this has been the consolidation of ornamental breeding companies to be able to effectively function on an international scale.Although in spite of this, within the ornamental breeding community, there are still a vibrant community of smaller breeding programs, independent breeders and hobbyist breeders who continue to make significant contributions to the commercial mix of ornamentals available (van Tuyl, 2012). In addition, in the USA and other countries, as the government has shifted from a philosophy of completely funding programs to assisting programs with partial funding (Frey1996; Heisey et al. 2001; Dolmans and van Reuter, 2013) and created granting programs linked to industry collaboration, public institutions began to create better linkages with the private sector. Thus granting success in breeding research is dependent on good private industry support.

Trends Affecting Ornamental Consumption

A breeding program needs to forecast the cultivar needs for the future and thus needs to be aware of the general trends that shape these needs. There are several broad trends that influence the breeding objectives of breeders.

One major trend is the environmental awareness of the public with respect to environmental contamination and health issues caused by the use of agrochemicals, agricultural sustainability, and concern over the availability of high quality water. In the produce industry, this is reflected in the mainstreaming of organic produce in our supermarkets (Byrne, 2012). In the ornamental industry, it has been shown that consumers are positively influenced to buy products that are labeled eco-friendly with such labels to indicate the production was raised with water conservation best practices, with the use of beneficial insects, organically produced, or with environmentally responsible practices (Schoellhorn, 2009; D’Allessio, 2015; Wollaeger et al., 2015; Khachatryan and Rihn, 2016; Rihn et al., 2016). In addition, signage to indicate the plant was bee-friendly, disease free, a native or non-invasive plant also positively influenced consumers to buy plants (Yue et al., 2010;Larsen and Orgaard, 2013; Wollaeger et al., 2015; D’Allesio, 2015; Khachatryan and Rihn, 2016;).

The other aspect of environmental responsibility is to assess the “carbon foot print” of production and use of ornamentals using a Life Cycle Assessment, which attempts to calculate the carbon cost of the product from production through harvesting, processing, marketing, consumption, and the disposal of any waste (Sim et al., 2007; Brentonet al., 2009).

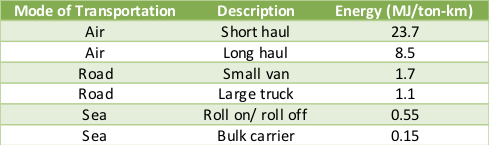

This type of analysis has indicated that even though a fresh product is produced several thousand miles away and has a high transport cost (Table 3), it does not mean that its carbon footprint is greater than locally produced product especially if the production costs are high, the product is not in season or it needs to be stored for an extended period. Good examples of this would be comparisons of the carbon foot print of cut flowers for Europe and produced in either the greenhouse in Holland or in Kenya (Brenton et al. 2009). This has led to more sustainable approaches of production which involves integrated pest/disease control, better use of water, nutrients, and energy, and more biodegradable packaging to decrease the amount of waste that needs to be disposed.

Consumer expectations drive the marketing trends. The consumer wants novelty, a diversity of products to choose from, high quality, and a long period of attractiveness. Once all that is in place, they want convenience. This would involve plants that are easy to plant, grow and maintain. They want to enjoy the garden without too much work (Schoellhorn, 2009; Grygorczyk, 2015; Watson, 2016).

To stay in business, a producer needs to produce high yields of a quality ornamental product for a minimum of expense both economically and from a management perspective. In ornamental production the two largest variable expenses are for labor and for agricultural chemicals to protect the crop from damaging diseases and pests. Thus the grower wants plants that are easy to grow, resistant to pests/diseases, widely adaptable, have a short growth cycle to harvest, high yielding, and can be managed to harvest at peak price points. The distributor wants plants that are easy to handle, have excellent post-harvest traits, extended attractiveness period, and are in high demand (Wilkins and Anderson, 2007; Schoellhorn, 2009).

A breeder has to satisfy all these needs to develop a successful cultivar.

Trends in Flower Breeding

There are six important trends in flower breeding:

- Adaptability

- Extended period of attractiveness

- Ease of propagation

- Diversity and novelty

- Postharvest excellence

- New breeding technologies

Adaptability

Of these, the strongest trend in established crops such as the garden rose would be the need for well-adapted plants. This was evident in a survey of the gardening community which indicated that the only very important trait they wanted in new garden rose cultivars was disease resistance (Fig. 1; Byrne, 2015). As consumers want to have a beautiful garden without working and without applying any pesticides or fungicides, the best ornamental plant cultivars have resistance to the prevailing biotic and abiotic stresses and maintain good growth and attractiveness continuously during the growing season. This includes resistance to various pests and diseases but also the ability to grow under the prevailing heat/water conditions (Dolmans and van Reuter, 2013; Pemberton and Karlik, 2015; Schoellhorn, 2015; Wilkins and Anderson, 2007). This has led many rose and other ornamental breeding programs to select for a wider range of stress tolerance in their cultivars and to more extensive trialing programs before the release of new cultivars or to independent regional no spray trials such as the various rose trial programs which include the Earth Kind, AGRS and ARTS programs in the USA and the ADR program in Germany (Zlesak et al., 2010; Byrne, 2015; Waering, 2017; Zlesak et al., 2017).

Fig. 1. Importance of rose traits from RHA-TAMU Rose Survey.

- 5 = most important

- 4 = very important

- 3 = important

- 2 = somewhat important

- 1 = not important

Data from online survey done in October to December, 2012.

Water quantity and quality are becoming a major challenge in many growing regions; much work needs to be done to reduce the use of water in both the production and use of ornamental plants. Currently 70% of the world’s fresh water supply is used in agriculture (Sansavini, 2009). This reality has spurred much research in better delivery (i.e. drip irrigation) and more efficient management techniques (real time weather monitoring linked to irrigation control). As more water restrictions are put on the use of water in landscapes, more needs to be done to develop the genetics that perform well with less and/or with poorer quality water (Cai et al., 2012; 2014).

Diversity and novelty

The ornamental breeding world, although a few dozen species are used extensively, is characterized by its use of hundreds of species. These species range over at least 250 genera and 100 families! This high diversity of plant materials has made it possible for the horticultural industry to create a continuous supply of new cultivars and crops for the garden and cut flower industries. This has been accomplished by introducing new species, new species hybrids, and new cultivars of standard crops constantly which has been possible due to good plant protection mechanisms and enhanced promotion of horticultural plants (Schoellhorn, 2009; van Huylenbroeck et al., 2012; Drew et al., 2015). Although many of the commercial cultivars are developed at large commercial breeding companies that have been merging to effectively work on an international scale, there are still a cadre of smaller breeding programs led by small companies, independent breeders and plant enthusiasts (hobbyists) involved in breeding ornamental plants which play an important role in creating this supply of novel plant materials for the ornamental markets (van Tuyl, 2012).

Extended period of attractiveness

The rose has developed into one of the most important ornamental crops in the world because it can repeatedly produce flowers throughout the growing season. Work continues to maximize flower production (both number per plant and frequency of rebloom) that a plant produces throughout the year especially under marginal growing conditions such as under high temperature conditions (Byrne et al.,2013; Greyvenstein et al., 2015; Liang et al., 2017a; b). This is an area that is pertinent to all flowering plants as the longer they flower the greater their desirability. This is especially important to the landscaping industry (Wilkins and Anderson, 2007; Schoellhorn, 2009; Roh, 2013). An example of flower extension for a woody shrub is the development of the extended season blooming azalea Encore series which had a huge impact on the azalea market (Sinopoli, 2005). Other examples would be the development of reblooming daylilies, irises, and lilies (Wilkins and Anderson, 2007).

Ease of propagation

Producers want plants that are less expensive to produce. In roses, there has been a shift in the industry from grafting plants towards rooting cuttings as it isa less expensive production technique (Pemberton and Karlik, 2015). In perennials there is a selection pressure to select for an annualized perennial which can be grown to the flowering stage in less than one year (Wilkins and Anderson, 2007). In many other species that have been propagated vegetatively, there are ongoing efforts to convert these into cultivars that are seed propagated to reduce production costs. Whatever the species or propagation scheme, to be commercially successful it must propagate efficiently with as short a cycle as possible (Schoellhorn, 2009; Blomerus et al., 2010; Roh, 2013) and thus this is an important selection criteria in ornamental breeding programs.

Post harvest excellence

As much of the cut flower production has moved to highland tropical zones and the sale of garden plants are shifting from local garden centers to mass marketing venues such as supermarkets, hardware stores, and other big box stores (Yue and Behe, 2009; Campbell and Hall, 2010; Dolmans and van Reuter, 2013; Hovhannisyan et al., 2017), there is more need to ship plant materials longer distances. Thus, there is a greater need for better post harvest qualities of the new cultivars (Blomerus et al., 2010), especially those sold as potted plants and cut flowers/foliage. Currently, most cut flowers from the tropical highlands are shipped to Europe or North America via air freight which is a 40-50 times more energy intensive than shipping by sea freight (Table 3). As global marketers go “green” and reduce their carbon footprint, there is a trend to transport ornamental products more via boat versus airplane, as this reduces the carbon footprint tremendously. This will require improved post-harvest characteristics of the ornamental cultivars.

New breeding technology

For most ornamental crops, as the diversity is great and little is known about their genetic background, the traditional breeding approach supplemented by embryo rescue and other techniques to enable the production of hybrids from wide crosses will predominate in the near future. The use of molecular approaches will be most frequently used for identification of hybrids and/or diversity analysis.

As the technology of low cost sequencing is developed this should make marker assisted breeding technology cost-feasible for some major crops such as rose, chrysanthemums, petunia, and carnations (Geike et al., 2012; Lutken et al.,2012; Debener and Byrne, 2014; Sharma and Messar, 2017). The use of improved transformation and designer nuclease technology has potential especially for disease resistance, flowering genes, color, growth types, ethylene control/sensitivity. These technologies have high potential and as compared to its use in food crops carries less negativity among the potential consumers (Debener and Byrne, 2014; Sharma and Messar, 2017).

Literature cited

Blomerus, L., S. Joshua and J. Williams. (2010) Breeding Proteaceae varieties for changing market trends. Acta Hort. 869:173-181.

Brenton, P., Edwards-Jones, G., and Jensen, M. F. (2009) Carbon labeling and low-income country exports: A review of the development issues. Development Policy Review 27(3), 243-267.

Byrne, D.H. (2015) Advances in rose breeding and genetics in North America. Acta Hort. 1064:89-98.

Cai, X., G. Niu, T. Starman, and C. Hall. (2014) Response of six garden roses (Rosax hybrida L.) to salt stress. Scientia Hort. 168:27-32.

Cai, X., T. Starman, and G. Niu. (2012) Response of selected garden roses to drought stress. HortScience 47:1050-1055.

Campbell, B.L., and C.R. Hall. (2010) Effects of pricing influences and selling characteristics on plant sales in the green industry. HortScience 45:575-582.

D’Alessio, N. (2015) Adding value to ornamental plants. American Nurseryman. Jan 12, 2015.https://www.amerinursery.com/american-nurseryman/adding-value-to-ornamental-plants/, Accessed July 22, 2017.

Debener, T. and D. H. Byrne. (2014) Disease resistance breeding in rose: Current status and potential of biotechnological tools. Plant Science 228:107-117.

Dolmans, N.G.M. and H. van Reuter. (2013) Challenges and perspectives for woody ornamentals. Acta Hort. 990: 27-35.

Drew, J., C. Yue, N.O. Anderson, and P.G. Pardey. (2015) Premiums and discounts for plant patents and trademarks used on ornamental plant cultivars: A hedonic price analysis. HortScience 50(6): 879-887.

Frey, K.J. (1996) National Plant Breeding Study: I. Human and Financial Resources Devoted to Plant Breeding Research and Development in the United States in1994. Special Report 98. Iowa State University.

Greyvenstein, O., H. B. Pemberton, T. Starman, G. Niu, and D.H. Byrne. (2014) Effect of two week high temperature treatment on flower quality and abscission of Rosa L. ‘Belinda’s Dream’ and ‘RADrazz’ under controlled growing environments. HortScience, 49 (6): 701-705.

Greyvenstein, O. T. Starman, B. Pemberton, G. Niu and D. H. Byrne. (2015) Development of a rapid screening method for selection against high temperature susceptibility in garden roses. HortScience. 50(12):1-8.

Grygorczyk, A., S. Mhlanga, and I. Lesschaeve. (2015) The most valuable player may not be on the winning team: Uncovering consumer tolerance for color shades in roses. Food Quality and Preference hyyp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2015.04.012.

Heisey, P. W., Srinivasan, C. S., and Thirtle, C. (2001) Public sector plant breeding in a privatizing world. Resource Economics Division, Economic Research Service, U. S. Department of Agriculture, Agriculture Information Bulletin No. 72.

Heyes, J. A. and Smith, A. (2008) Could “Food Miles” become a non-tariff barrier? ActaHort. 768, 431-436.

Hovhannisyan, V., and H. Khachatryan. (2016) Ornamental plants in the United States: Aneconometric analysis of a household-level demand system. Agribusiness33:226-241.

Khachatryan, H. and A. Rihn. (2016) Florida consumer preferences for ornamental landscape plants. IFAS. FE1000.

Larsen, B., and M. Orgaard. (2013) Native herbaceous perennials as ornamentals: an upcoming trend. Acta Hort. 980:103-109.

Liang, S., X. Wu, and D.H. Byrne. (2017a). Flower-size heritability and floral heat-shock tolerance in diploid roses. HortScience. 52(5):1-4.

Liang, S., X. Wu, and D. H. Byrne. (2017b) Genetic analysis of flower size and production in diploid rose. J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 142(4):1-8.

Pemberton, H.B. and J.F. Karlik. (2015) A recent history of changing trends in the USA garden rose plant sales, types, and production methods. Acta Hort. 1064:223-234.

Rihn, A., H. Khachatryan, B. Campbell, C. Hall, and B. Behe. (2016) Consumer preferences for organic production methods and origin promotions on ornamental plants: evidence from eye-tracking experiments. Agric. Econ. 27:599-608.

Roh, M.S. (2013) The direction of new floral crops research – Reflections on the past and future prospects. Acta Hort. 1000:569-578.

Sansavini, S. (2009) Horticulture in Europe: from history to innovation. Acta Hort. 817, 43-58.

Schoellhorn, R. (2009) Strategies for plant introduction and market trends in the US. ActaHort. 813:101-106.

Sharma, R. and Y. Messar. (2017) Transgenics in ornamental crops: creating novelties in economically important cut flowers. Current Science 113(1): 43-52.

Sim, S., Barry, M., Clift, R., and Cowell, S. J. (2007) The relative importance of transport in determining an appropriate sustainability strategy for food sourcing. Intern. J. LCA 12 (6), 422-431.

Sinopoli, J. (2005) Azalea fascination yields market success. Amer. Nurseryman. 2005(Jan):22 .

Traxler, G., (1999) Balancing basic, genetic enhancement and cultivar development research in an evolving US plant germplasm system. AgBioForum 2(1), 43-47.

Van Huylenbroeck, J., E. Calsyn, A. van den Broeck, and R. Denis. (2012) Breeding new flowering ornamentals: the Bicajoux story. Acta Hort. 953:135-138.

van Tuyl, J. M. (2012) Ornamental plant breeding activities worldwide. Acta Hort. 953:13-17.

Waering, G. (2017) 2018 American Garden Rose Selections. American Rose, March/April: 57-58.

Waliczek, T. M., Byrne, D. H. and Holeman, D. J. (2014) Growers’ and consumers’ knowledge, attitudes and opinions regarding roses available for purchase. ActaHort. 1064:

Watson, C. (2016) Landscape trends and opportunities. GPN March: 18-21.

Wilkins, H., and N.O. Anderson. (2010) Creation of new floral products. Annualization of perennials – Horticultural and commercial significance, p. 49-64. In Anderson, O. (Ed.). Flower breeding and genetics. Issues, challenges and opportunities for the 21st century. Springer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

Wollaeger, H.M., K.L. Getter, and B.K. Behe. (2015) Consumer preferences for traditional neonicotinoid-free, bee-friendly, or biological control pest management practices on floriculture crops. HortScience 50:723-732.

Yue, C., and B.K. Behe. (2009) Factors affecting U.S. consumer patronage of garden centers and mass-merchandisers. Acta Hort. 831:301-308.

Zlesak, D. C., Whitaker, V. M., George, S. and Hokanson, S. C. (2010) Evaluation of roses from the Earth-Kind trials: black spot (Diplocarpon rosae Wolf)resistance and ploidy. HortScience 45: 1779-1787.

Zlesak, D.C., M. Schwartz, G. Hammond, R. Nelson, M. Chamblee, S. George. (2017) Rating Roses: A new American rose trialing program — American Rose Trials for Sustainability®. Amer. Nurseryman 217(5).