What is a Rose?

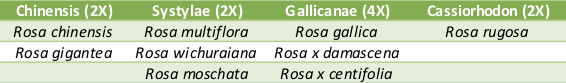

Understanding the organism with which one works is essential for consistent success. The cultivated rose is a multispecies complex that contains mainly diploids, triploids and tetraploids. It is generally stated that 8 to 10 main species have been used in the development of the modern commercial rose. Currently the about half of the commercial roses are tetraploids (~45%) but with a substantial number of triploids (~25%) and diploids (~30%).

Roses are native to the Northern Hemisphere (mainly Asia, Europe, North America) and were domesticated independently in China and Europe. It was in China where the remontant, or everblooming, rose was first discovered. The early European roses were mainly non-remontant, or spring blooming, with only a repeating bloom in the fall. Thus, when remontant Chinese roses were brought to Europe, there was much excitement. It was the introgression of Chinese roses and the European roses that lead to the development of the modern remontant blooming rose that we know today. Initially, the bees did the work of pollination among the roses and later a human hand intervened to accelerate the process.

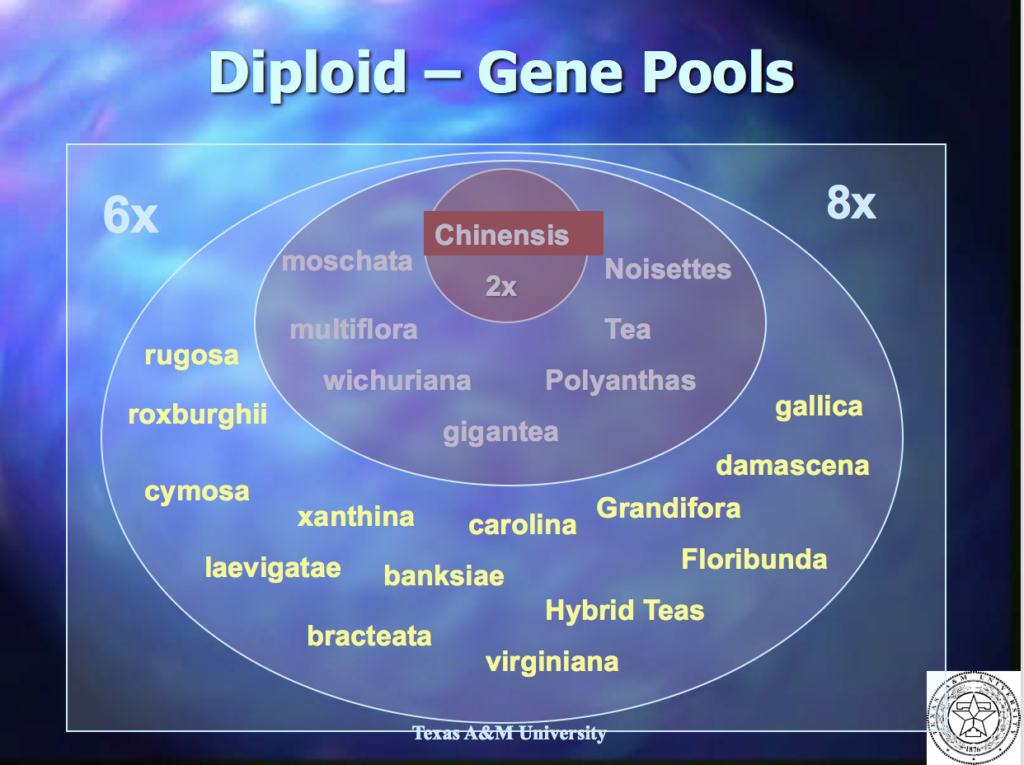

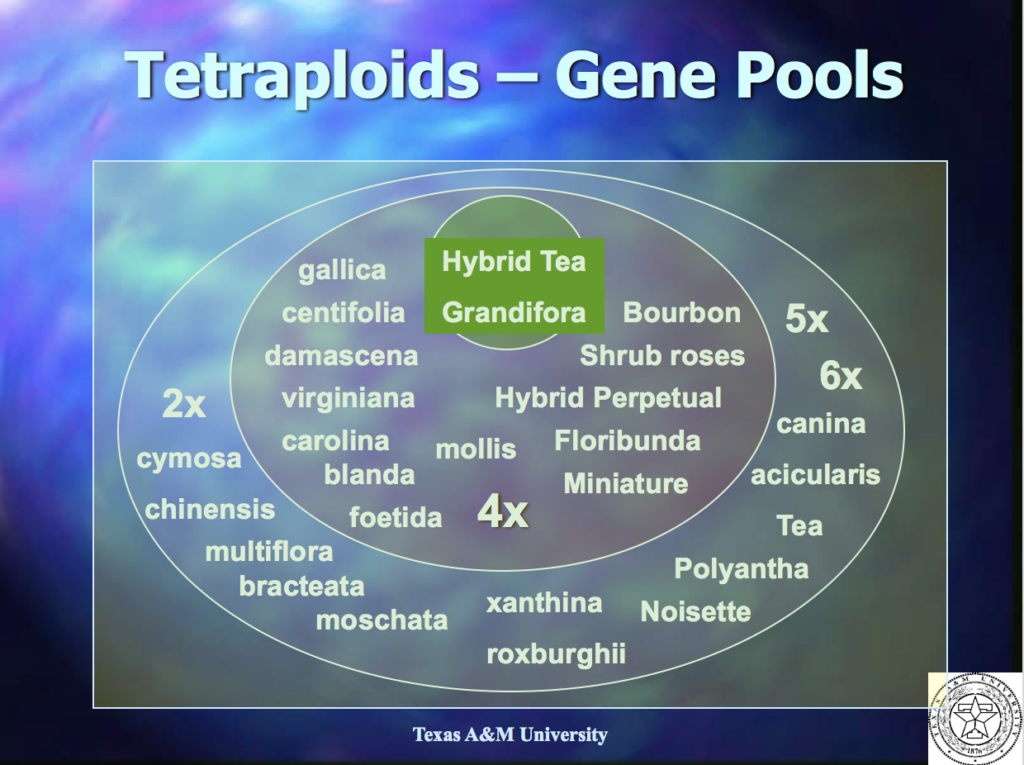

The rose germplasm that a breeder has accessible is wide especially as many species intercross to give fertile seedlings or at least fertile enough to make a few crosses. When looking at rose germplasm, we can look at it from a diploid perspective or a tetraploid perspective.

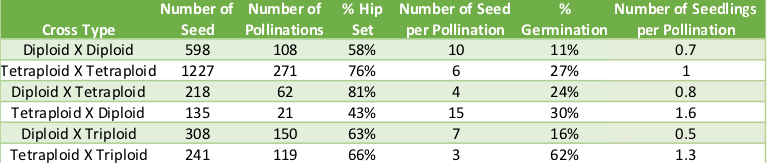

As breeders tend to cross among a wide range of roses in their work, it is not unusual to make interploidy crosses especially in the development of garden roses. This is common because the success rate is good. In recent work done at Texas A&M University, we found that among same ploidy crosses the crosses at the diploid level produce fewer seedlings per pollination mainly due to a much lower germination rate than seen at the tetraploid level. For the interploidy crosses between diploids and tetraploids, again using the diploid as the female parent tends to give fewer seedlings per pollination but this time mainly due to fewer seeds produced per hip. Breeders frequently use triploid parents (‘Knock Out’, ‘Homerun’, ‘Little Buckaroo’, ‘Iceberg’, ‘Innocencia Vigorosa’, ‘Pink Drift’, etc.) as parents as well. According to our work with crosses with ‘Homerun’, there was good success using the triploid as a pollen parent. Again, more seedlings per pollination were produced when the female parent was a tetraploid as compared to the success with a diploid female (Table 1).

Traditional rose breeding is basically a recurrent phenotypic mass selection program. Thus parents are selected with the desired traits in the hope that one of the hybrid seedlings from the cross will combine multiple traits from the different parents to result in a rose that is better than the parent. Then the best seedlings are used in the crosses to continue concentrating the best genes into one package which results into a superior rose cultivar. Such a program is creating new populations every year and generating better materials every year. It is a continuous process of improvement and the introduction of new genetics into your breeding population to prevent a stagnation in progress.

The most common mistakes made in plant breeding are the following:

Failure to measure traits properly. Although this seems obvious, the ability to measure a trait is essential for selection. Many traits such as plant or flower size, the number of prickles, and plant structure can be measured consistently over years and sites. However, traits such as disease resistance or winter cold tolerance may depend on the environmental conditions for expression. With these traits, one may have to wait several years for a “good” year for measurement. These traits are more challenging and thus more expensive to measure.

Failure to start at most advanced level. In a situation in which you want to develop a shrub rose that is resistant to a disease, you might have several sources of resistance ranging from a diploid wild species to a well adapted commercial cultivar. The quickest progress towards a commercial variety would be to use the source of resistance from the source with the best horticultural traits.

Failure in breath. This is complementary to the above mistake. Any breeding program is developing products for the future which we try to predict but not always accurately. Whether it is developing specific horticultural traits or developing sustainable roses, we need to take a broad look at what might be desirable for future rose cultivars. The desirable horticultural look varies over the years, at times, unpredictably. Recently, there has been a strong trend for sustainable rose cultivars which means we need the new cultivars to be stable in their resistance to the disease. The challenge here is that the pathogen is changing over time as well. Thus, to ensure stable resistance, several sources of resistance need to be pursued simultaneously. In the case of disease resistance when there are sources of resistance from commercial and species materials, the first push would be to develop varieties by using the commercial sources but work should also be done to begin incorporating the resistance from the species accessions into the commercial germplasm.

Failure to move through generations. Sometimes, certain parents result in a high proportion of excellent seedlings so a breeder uses it extensively. This will result in variations on a theme which is useful to develop a series of similar roses with varying colors, flower type, or plant habits. Commercially, this is a very useful strategy in plant breeding. Nevertheless, it does not lead to great progress in breeding but to a type of stagnation. Thus, one always should be using new and hopefully improved selections derived from those excellent parents and introgressing new germplasm into your breeding populations.

Failure to eliminate ‘losers’. It is expensive to do field trials so you want to limit the number of new selections that are propagated for further evaluation and of those whittle down that population as quickly as possible. Keeping selections that are almost good enough is not a good strategy. Anything kept needs to have a reason to be kept. As Dr. Hough, a fruit breeder at Rutgers University and my first breeding mentor would say, “if in doubt, throw it out!”.

Field Evaluations

The scale that we use to evaluate roses in the field is based on the presence of disease, the flower quality, and the plant’s overall performance.

Disease Rating: Black Spot – Powdery Mildew

- 0=no mildew on plants

- 1=one or two isolated infections

- 2=slight infection throughout plant

- 3-7=based on the percentage of leaves infected

- 8=infection present on most of the foliage, stems, and peduncles

- 9=heavy infection throughout plant

Flower Evaluation: Intensity

- 0=no flowers

- 2=20% of plant surface develops flowers

- 5=50% of plant surface develops flowers

- 7=70% of plant surface develops flowers

- 9= over 90% of plant surface develops flowers

Flower intensity should be observed at least monthly, and each evaluation period should consider optimum intensity in order to avoid bias due to the time of evaluation.

The best ratings occurred when the flowers were displayed above the foliage.

Flower Evaluation: Cleaning

- 0=flower does not lose petals and balls (ex. Belinda’s Dream), needs deadheading

- 5=good cleaning, petals tend to turn brown before falling

- 9=petals fall cleanly before turning brown or ugly

Overall Rating: Landscape Performance

- 5=large leaf loss and weak plant with excess of dead wood

- 4=large leaf loss and weak plant, but with less dead wood and shows signs of vigor

- 3=large leaf loss but has good vigor and little dead wood

- 2=some leaf loss but with little disease and good landscape appearance

- 1=little if any disease, good vigor with little or no disease loss, outstanding landscape appearance

Ratings 5 and 4 were deemed unacceptable. Rating 3 shows good regrowth potential and might work with some chemical disease control. Rating 2 is the minimum for Superstar status. Rating 1 is reserved for outstanding varieties.